Health Care Costs

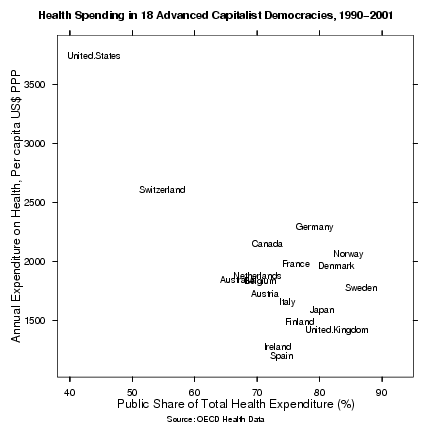

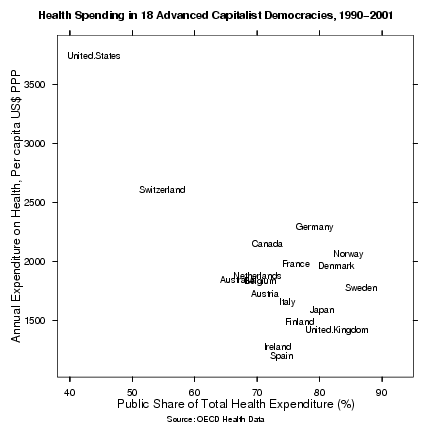

Kieran Healy displays a chart purporting to show that health care expenditures per capita are the highest in those countries (especially the U.S.) that have lower expenditures by the government. Here's the chart:

Healy says:

If we spend twice as much per capita on health care -- so what? What does this tell us about the increase in quality that we should expect at the margin? I don't know.

Indeed, I suspect that the situation is worse in trying to analyze health care. One person's healthcare might feature a higher price and a worse outcome -- but without any malfunction in the healthcare system itself. Compare two hypothetical people: Person A in Country A spends $100 on an office visit where the doctor tells him to eat healthy and non-fatty foods. Person B in Country B spends the same $100 on the same office visit, but decides to eat unhealthy foods anyway. Sometime later, he ends up spending $40,000 on heart bypass surgery, and ends up dying anyway. If you just look at the figures and the outcomes, you might be misled into thinking, "Gee, Country B spent $40,100 where Country A spent $100, and the mortality rate was still higher." But -- in this hypothetical -- there is nothing inadequate about either country's health-care nor about their systems of expenditure. The only difference is due the Person B's lifestyle choices.

That's not to say there aren't important differences in health care and expenditures across various countries. It is just to say that there may well be choices in lifestyle and diet that have a huge effect on how much health-care a country has to provide. Unless you control for those factors, the mere level of expenditures says little.

Moreover, buying more healthcare might worsen outcomes. More visits to the doctor or more days in the hospital is not necessarily a good thing. It also means more possible interactions with other sick people carrying communicable diseases, plus the risk of catching something from a nurse or doctor who didn't wash her hands. The CDC claims that 2 million people get infections from the hospital annually. An NYU doctor estimates that 50 million antibiotic prescriptions annually are completely unnecessary, and only contribute to the growth of antibiotic-resistant bacteria. If all of those prescriptions averaged $20 apiece, there's an expenditure of $1 billion that actually harms the nation's health.

Then there's the fact that some people experience adverse reactions to the medical treatment itself. One JAMA study theorized that the U.S. might incur 100,000 deaths per year due to adverse reactions to prescribed drugs. (Think about that next time a politician praises the federal government's new involvement in paying for prescription drugs.) Then there is medical error: According to the National Institute of Medicine, medical errors might account for 44,000 to 98,000 deaths per year.

The moral is that it is very difficult to tell whether one country is getting more for its money than another. There are so many variables involved (including the patients' own choices), and so many ways that more health care could actually be a negative thing. How do we know what the "proper" level of spending is, and whether we're actually getting our money's worth?

* * *

Kevin Drum further discusses the chart here, and concludes:

What might make one country spend half as much money on health-care as another? Various reasons spring to mind:

1) It might buy less health-care, i.e.,fewer surgeries and doctor visits, fewer tests, fewer drugs, etc., etc. This is the most obvious explanation, and as stated above, less health-care overall might be a positive thing in many circumstances.

2) Administrative costs might be lower.

3) Doctors' salaries might be lower.

4) People might make better lifestyle and dietary choices that result in less health-care expenditure per capita.

5) The country in question might free-ride on other countries' research into treatment.

6) The lower-cost country might be more productive (e.g., they can complete a given surgery with just one doctor and an anesthesiologist, as opposed to half a dozen people).

Any others?

In any event, the sorts of people who make cross-country comparisons of health care costs often seem to think -- for what reason, I don't know -- that the entirety of the explanation lies in number 2: Administrative costs. Thus, they'll argue that France or Britain has a more centralized system with lower administrative and paperwork costs, and if only we adopted their system, we too could provide healthcare to more people for half the money.

But I doubt that this could possibly be true. Administrative costs are significant, but I just don't think that administrative costs could be what explains why Britain spends $1500 per person on health care while the United States spends around $3600. Could paperwork and administration really account for $2100 per person?

I suspect that all of the factors are involved to some extent, which makes me skeptical of any claim that a mere change in the method of payment will result in a magical cure for all our problems: Greater health care for less money. The situation has to be more complicated than that.

Healy says:

As you can see, health care in other advanced capitalist democracies is typically twice as public and half as expensive as the United States. . . . There’s not much evidence that the quality of care in the U.S. is twice as good as everywhere else.Well, one wouldn't expect twice the expenditure to deliver twice the quality of any good. Price and quality are not linearly related. In any endeavor in life, more effort and expense is spent to make the last 1% of improvement than the first 1%. It is far, far easier for a 12 minute miler to reduce his time to 11:50, than for a 3:50 miler to reduce his time to 3:49. The increase in quality between a $5,000 car and a $10,000 car is probably more than the increase in quality between a $50,000 car and a $100,000 car.

If we spend twice as much per capita on health care -- so what? What does this tell us about the increase in quality that we should expect at the margin? I don't know.

Indeed, I suspect that the situation is worse in trying to analyze health care. One person's healthcare might feature a higher price and a worse outcome -- but without any malfunction in the healthcare system itself. Compare two hypothetical people: Person A in Country A spends $100 on an office visit where the doctor tells him to eat healthy and non-fatty foods. Person B in Country B spends the same $100 on the same office visit, but decides to eat unhealthy foods anyway. Sometime later, he ends up spending $40,000 on heart bypass surgery, and ends up dying anyway. If you just look at the figures and the outcomes, you might be misled into thinking, "Gee, Country B spent $40,100 where Country A spent $100, and the mortality rate was still higher." But -- in this hypothetical -- there is nothing inadequate about either country's health-care nor about their systems of expenditure. The only difference is due the Person B's lifestyle choices.

That's not to say there aren't important differences in health care and expenditures across various countries. It is just to say that there may well be choices in lifestyle and diet that have a huge effect on how much health-care a country has to provide. Unless you control for those factors, the mere level of expenditures says little.

Moreover, buying more healthcare might worsen outcomes. More visits to the doctor or more days in the hospital is not necessarily a good thing. It also means more possible interactions with other sick people carrying communicable diseases, plus the risk of catching something from a nurse or doctor who didn't wash her hands. The CDC claims that 2 million people get infections from the hospital annually. An NYU doctor estimates that 50 million antibiotic prescriptions annually are completely unnecessary, and only contribute to the growth of antibiotic-resistant bacteria. If all of those prescriptions averaged $20 apiece, there's an expenditure of $1 billion that actually harms the nation's health.

Then there's the fact that some people experience adverse reactions to the medical treatment itself. One JAMA study theorized that the U.S. might incur 100,000 deaths per year due to adverse reactions to prescribed drugs. (Think about that next time a politician praises the federal government's new involvement in paying for prescription drugs.) Then there is medical error: According to the National Institute of Medicine, medical errors might account for 44,000 to 98,000 deaths per year.

The moral is that it is very difficult to tell whether one country is getting more for its money than another. There are so many variables involved (including the patients' own choices), and so many ways that more health care could actually be a negative thing. How do we know what the "proper" level of spending is, and whether we're actually getting our money's worth?

* * *

Kevin Drum further discusses the chart here, and concludes:

Basically it shows that the United States has (a) much less public involvement in healthcare than the other countries and (b) much higher healthcare costs.The conclusion one is supposed to take from the chart isn't readily obvious. Drum seems to imply that it would be possible to deliver better care at half the cost. This seems implausible.

* * * Note that the chart doesn't really demonstrate any special trend, but it does show that conservatives who insist that national healthcare systems are nothing more than vast boondoggles that inevitably produce huge amounts of waste and higher costs just isn't looking at the evidence. As near as I can tell, France has a better healthcare system than the United States on practically every measure, and does it at half the cost.

What might make one country spend half as much money on health-care as another? Various reasons spring to mind:

1) It might buy less health-care, i.e.,fewer surgeries and doctor visits, fewer tests, fewer drugs, etc., etc. This is the most obvious explanation, and as stated above, less health-care overall might be a positive thing in many circumstances.

2) Administrative costs might be lower.

3) Doctors' salaries might be lower.

4) People might make better lifestyle and dietary choices that result in less health-care expenditure per capita.

5) The country in question might free-ride on other countries' research into treatment.

6) The lower-cost country might be more productive (e.g., they can complete a given surgery with just one doctor and an anesthesiologist, as opposed to half a dozen people).

Any others?

In any event, the sorts of people who make cross-country comparisons of health care costs often seem to think -- for what reason, I don't know -- that the entirety of the explanation lies in number 2: Administrative costs. Thus, they'll argue that France or Britain has a more centralized system with lower administrative and paperwork costs, and if only we adopted their system, we too could provide healthcare to more people for half the money.

But I doubt that this could possibly be true. Administrative costs are significant, but I just don't think that administrative costs could be what explains why Britain spends $1500 per person on health care while the United States spends around $3600. Could paperwork and administration really account for $2100 per person?

I suspect that all of the factors are involved to some extent, which makes me skeptical of any claim that a mere change in the method of payment will result in a magical cure for all our problems: Greater health care for less money. The situation has to be more complicated than that.

9 Comments:

Back on 9/30/03, a blogger posted 2 links, one to al Guardian comparing 4 diseases and survival rates between Britain and US.

The other link was a study, IIRC, of certain cancer survival rates between US and Western European countries broken down by country and male/female.

Guess who had the best survival rates????

Of course, it could be 9/30/02.

I'm sorry I didn't save either, but for some reason, I remember that date. Maybe they want to do some research?

Sandy P.

Who knows, maybe there's some "risk homoestatis" going on. In a country where people think, "If something happens, the doctors will fix it," they may be more likely to ignore that advice to eat healthier and get more exercise. "I'll get a blood pressure drug and a cholesterol drug and ...."

You left out a huge reason-healthcare costs spent in this last year of life. I remember some study somewhere that a huge percentage of healthcare costs are spent on people in their last year of life. A simple change in philosophy ("well, that third round of chemo will probably do more harm than good") would save a lot of money. The downside is a person might not squeeze out a few more months in agony.

This would be a big change. A good friend of mine bragged about how his dad was a fighter and gave it is all- I nodded my head and wondered if I would just try to spend some quality time with my family versus medical specialists. Obviously my friend would not. A more cynical view is that doctors do the math and know that "doing their all" provides them with the Aspen lodge and the beachouse.

When those socialist countries put people on waiting lists, I think they know damn well that a lot of people won't be around when their turn comes. That keeps the costs down.

Some economist found that when public education was established in Britain and the U.S., total investment in education decreased. The model they used to explain this is that under private funding, people willingly paid for an equilibrium quality q, but when a free alternative sprang up of lower quality q* (say, q/2), they switched to that. And once you're in public education, you can't improve quality by spending an additional marginal dollar.

Something like that is probably happening in health care. The resources that foreign governments put into health care compete with higher-quality forms of care, while in the US the govt's money supplements private high-quality care. So in the US govt funding increases the equilibrium quality of care consumed, while in socialized health-care countries it generally decreases it.

1) Do "U.S. health care expenditures" include plastic surgery, fat farms, drug rehab, etc.? 2) Remember that when foreigners come to the U.S. for health care, that gets counted as a U.S. health care expenditures.

Stuart,

I think the team doing the best work on this issue is Uwe Reinhardt (Woodrow Wilson School) and Jerry Anderson and Peter Hussey (Johns Hopkins School of Public Health). They constantly reanalyze the latest OECD health spending data and publish on this issue all the time in Health Affairs -- most recently, "U.S. Health Care Spending in An International Context." Briefly, that article discusses the following reasons for higher U.S. health care costs:

1--GDP per capita -- greater ability to pay;

2--Much higher professional labor costs;

3--Much lower buying power due to the fragmented multi-payer structure of the U.S. health care system;

4--Lower supply of health professionals;

5--Somewhat lower supply of hospital beds and healthcare technology (surprising to me, but it's true when compared to, e.g., Japan);

6--Complexity of financing structure leading to high administrative costs;

7--Unwillingness to ration health care.

On that last point, and in reference to a comment above, it's been a while since I looked at it, but I think Daniel Callahan's discussion of his term the "ragged edge of life" in his book "What Kind of Life" provides an elegant way to think about health care "needs" and rationing.

Note also Peter H. and Jerry A. of the Johns Hopkins group have recently been publishing a lot on cross-country health care quality comparisons. Very interesting stuff, I think.

If the government gave everyone a free Hyundai, you'd see the country's per capita expenditure on automobiles decline, as people who prefer, say, Audis to Hyundais when paying full cost, come to prefer free Hyundais to $30k Audis.

That's what the countries clustered around 80% public health expenditures do - they offer free low-quality health care and make people pay full freight to go outside the socialized health system.

Shouldn't the costs of litigation factor in here too? The malpractice insurance rates for all parties involved in health care are a bit higher in the US than most (or all) other countries.

Dan S

Health care costs in the U.S will never go down. The incentives are all in the wrong direction. There are no standards.Cost per incremental improvement in quality of life per diagnosis. Hence MRIs and surg-centres and CT scans are sprouting on every street corner. I know. I am a retired MD.The answer is simple. Have every physician's "test ordering profile" and "cost index per diagnosis per patient" become publicly available on-line; as well as the compensation packages of all health-care company executives and promotional incentives offered by the biotech and pharmaceutical industries.

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home